The Power of Pinpointing Earthquakes on the Central Coast of British Columbia

How one new seismometer shakes up our understanding of tectonics in the province.

As in real estate, “location, location, location” is essential to understanding an earthquake. Determining the origins of ground motion helps scientists understand geologic hazards from landslides to potential for tsunami. But obtaining this information relies on a robust sensor network used to triangulate the source—and the network on the Central Coast of British Columbia just got a key upgrade.

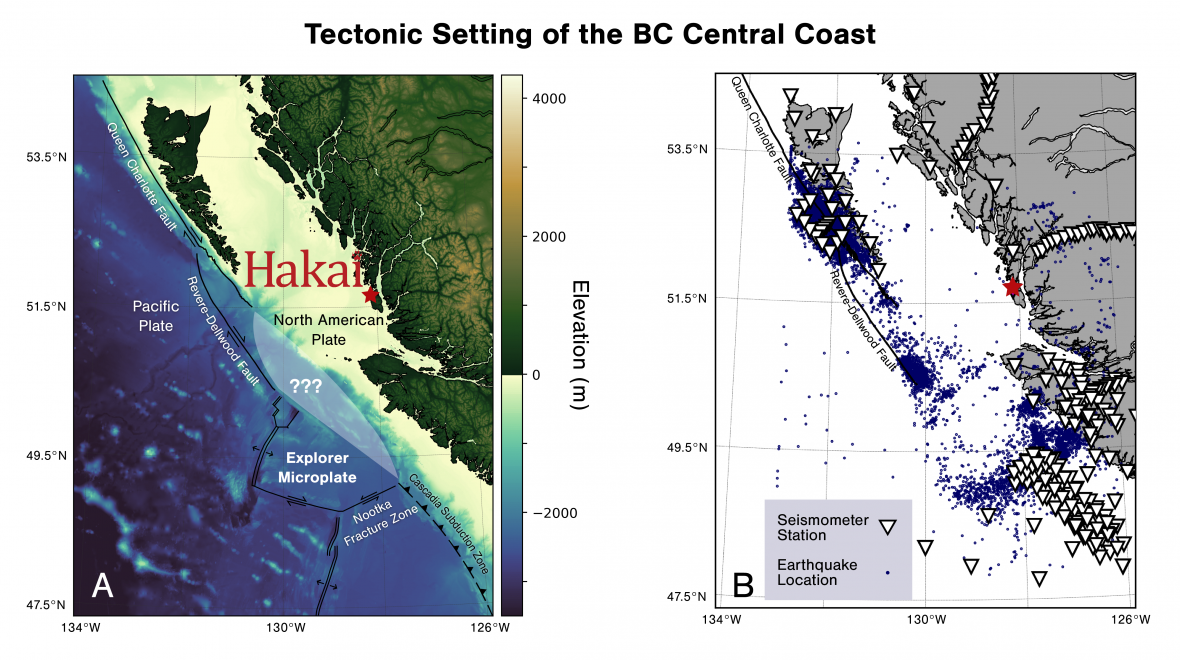

“There was a bit of a gap between [seismometers near] Port Hardy and Bella Bella,” says Andrew Schaeffer, a research scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) and adjunct professor at the University of Victoria.

The Hakai Institute’s Calvert Island Ecological Observatory sits conveniently between these sensors and a partnership was forged between the University of British Columbia (UBC), the GSC, and the Hakai Institute to fill the gap.

“It was a blast from the past,” says Hakai’s Shawn Hateley, who was part of the team installing the seismometer on Calvert Island this fall. As it so happens, Hateley, a jack of all trades, had previously installed similar seismometers in New Zealand. “It was really fun to work on.”

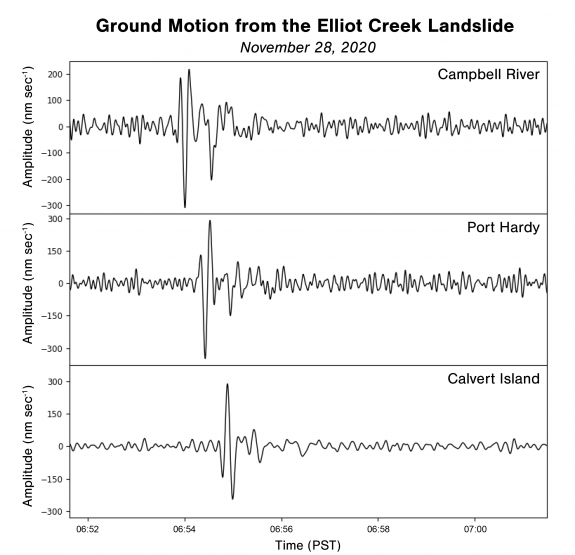

The Calvert Island seismometer, which streams data in real time, has already contributed to pinpointing locations of notable earthquakes in Alaska and Haida Gwaii. It has also helped scientists retroactively determine when a massive landslide occurred in the early morning of November 28 near Elliot Creek, a tributary to Bute Inlet. Using that time as a starting point, a global team of scientists is now piecing together the events of the slide and measuring its effects on the inlet and beyond.

While massive landslides are uncommon, the Central Coast is home to what is perhaps Canada’s most active seismic region just off Calvert Island. With over 100 earthquakes a year, the edges of the Explorer Microplate are grinding against the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate.

Despite all this seismic activity, scientists still don’t have a clear picture of the Explorer Microplate’s coastal boundary with North America. The microplate could either be shearing apart due to deformation (strike-slip faulting), or it could be diving beneath the continent (subduction faulting). The distinction is critical, as subduction zone earthquakes can lead to devastating tsunami, while shearing earthquakes offshore are generally less hazardous.

“Up till now, getting an accurate location [of earthquakes] offshore has been hard to get,” says Michael Bostock, a professor at UBC.

The newly installed seismometer could improve the estimate of an earthquake’s three-dimensional location by about 25 percent, according to Schaeffer, and importantly reduces the minimum earthquake magnitude that can be located offshore. And it isn’t only future earthquakes that will benefit from more precise locations.

“You can improve all the locations [in the record] when you start improving the locations from here forward,” says Bostock.

This is possible because the data from Calvert Island’s seismometer provides new information on how seismic energy moves through the crust with each earthquake.

Like putting a pair of glasses on the existing data set, Bostock’s doctoral student Geena Littel will then be able to use statistics to reanalyze 20,000 earthquakes from the last 25 years. More precise earthquake locations will bring the microplate’s fault lines into sharper focus, which will allow Littel to create a model of the Explorer Microplate’s structure, a process known as seismic tomography.

The Calvert Island seismometer “provides the independent evidence needed to either support subduction of the Explorer Microplate or be a line of evidence against it,” notes Littel.

If the results suggest only shearing earthquakes are at the boundaries of the microplate, as Bostock suspects, then coastal residents may rest a little easier knowing that earthquakes offshore are unlikely to generate a tsunami—essential information for hazard planners in coastal communities.

“Working with Hakai has been a perfect opportunity to solve some of these big outstanding questions [in BC geology],” says Schaeffer.

Real-time data from the seismometer is acquired by the GSC in Sidney, and made available through the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS) data portal.