Digital Tools Reveal Ancient Art

A digital imaging tool is allowing Aurora Skala to see rock art invisible to the naked eye.

Aurora Skala was on a mission. Armed with a written description, a crude drawing, and some hints from locals, she was hunting for a site she’d been looking for over the years, thus far to no avail. This was Indiana Jones anthropology, searching by boat through the dense rainforest for an ancient cultural treasure.

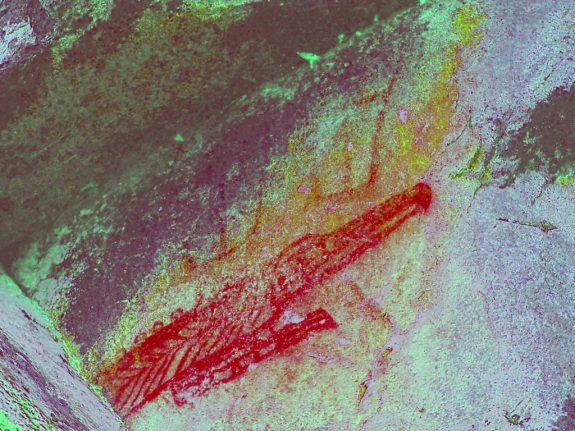

Then, something. From the corner of her eye she spotted a flash of red, and nearly ignored it. Unsure, she asked the boat driver to turn around, and there it was: a rock painting of a Wuikinuxv motif so powerful that it has persisted through time and is still used today.

Ancient rock art is scattered throughout the Central Coast, hidden gems painted on rock faces. When they’re found, the pictographs can tell stories from the First Nations of the area, and even hundreds of years later can contain symbols and motifs still used today – but finding them is a challenge.

“They are sometimes covered by water, or trees, or lichen, or moss, which have blocked them since they were created,” says Skala, a Master’s of Anthropology student at the University of Victoria. “With pictographs, especially on exposed rock faces, they are vulnerable to weather and erosion.”

But now Skala has found a way to reveal these faded works of art using digital imaging technology.

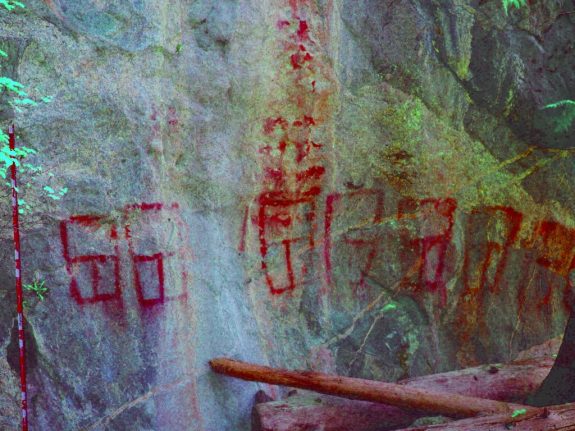

An application called DStretch has allowed Skala to enhance nearly invisible details until faded shapes become clear. DStretch was developed specifically for the purpose of enhancing faded rock art, essentially by pushing the image’s contrast to the extreme.

“I saw a presentation by [Hakai scholar] Duncan McLaren where he used DStretch to bring out additional images in a Heiltsuk pictograph which could only be faintly seen with the naked eye,” Skala recalls. “I actually got goosebumps seeing it. I was just so inspired I knew that I wanted to use that tool in my own research.”

She went out and started experimenting. She soon discovered that a Wuikinuxv eagle painting actually had two coppers (art used during potlatches) above it, so faded as to be invisible to the eye. Using DStretch she even accidentally found art on apparently bare rock.

In partnership with the Heiltsuk and Wuikinuxv First Nations, Skala has added 11 rock art sites to the known sites in the region. Using DStretch she has even found pictographs on rocks she didn’t know had anything on them at all.

Research like Skala’s can also help place ancient art in a broader historical and cultural context. Dating the art would make it possible to add it to a chronology of designs and themes, contributing to an understanding of cultural development and interaction through time.

Dating the art is a complicated task, however, and some techniques can damage the sensitive sites, which are hundreds or even thousands of years old. For now, Skala prefers to focus on finding the sites, many of which have never been photographed before, and applying DStretch to reveal even more about these remarkable works of art.

“When archaeologists excavate, the nature of the technique is destructive,” she says. “But with photographs, future research could still be done as techniques improve.”

“Because I am not touching the rock art I haven’t screwed it up for someone down the road who might have a better technique to try.”

Before and after examples of using DStretch on pictographs in Wuikinuxv territory. Photographs not to be reproduced without permission from Aurora Skala and Wuikinuxv Nation.