Crossing Ocean Borders

International scientific collaborations are key to understanding our changing oceans.

Ocean currents don’t clear customs when they cross political boundaries. Neither did the marine heatwave, nicknamed the Blob, which caused widespread ecosystem disruption in both the United States and Canada. That’s why international collaboration is vital to better understand our changing oceans. That kind of cross-border cooperation is exactly what’s happening in the northeast Pacific and beyond.

“By working together with American scientists, we can study processes that impact the whole coastline,” says Hakai scientist Jennifer Jackson.

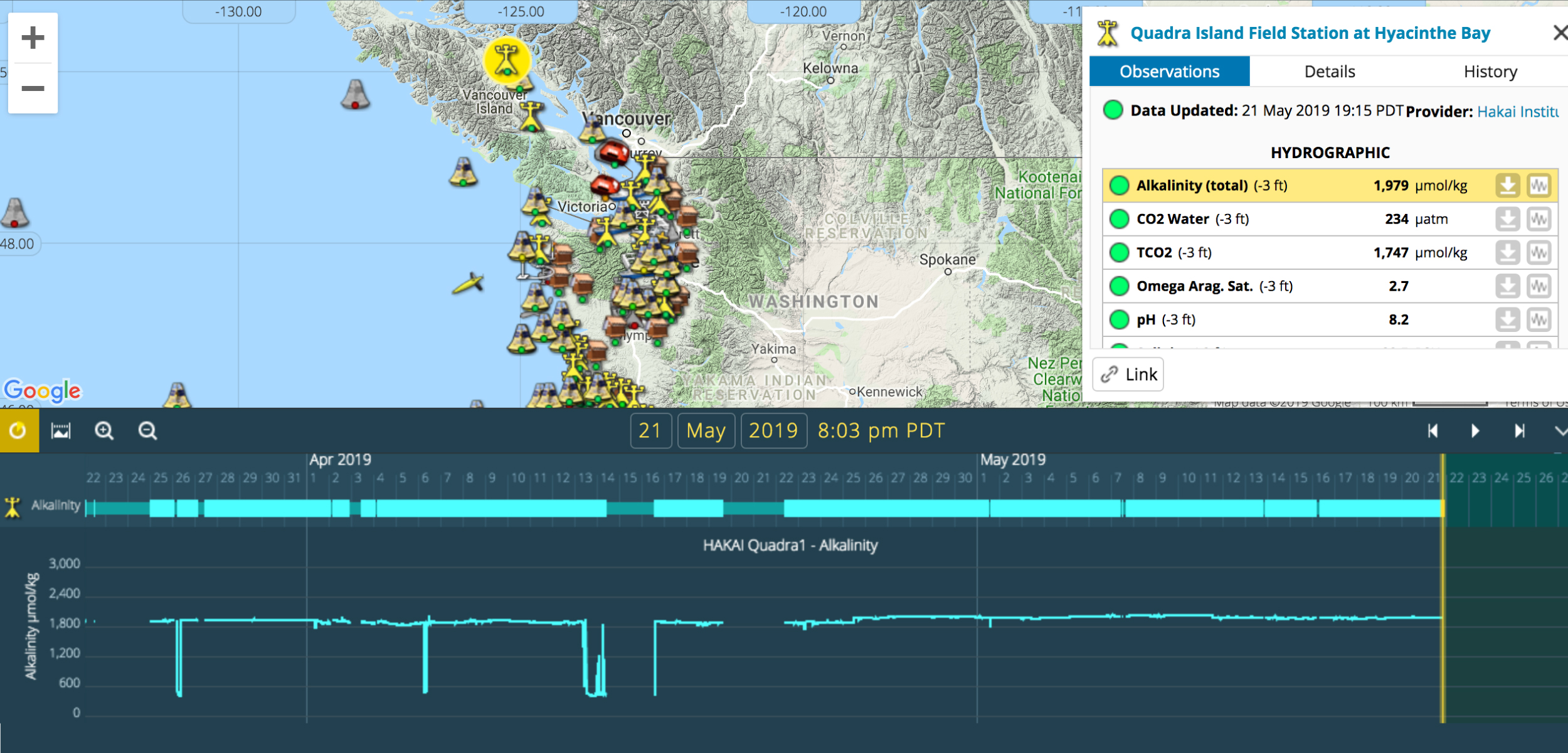

Jackson and fellow Hakai scientists are starting to see positive momentum when it comes to partnerships. One area where cooperation is at the forefront is sharing oceanographic data through what are called ocean observing systems (OOSes).

For the past few years, Canadian oceanographic data from the Hakai Institute has been incorporated into two American-based OOSes—NANOOS and AOOS—the Pacific Northwest and Alaska systems. But now Canada is getting its own OOS.

In early March, Fisheries Minister Jonathan Wilkinson formally announced the formation of the Canadian Integrated Ocean Observing System (CIOOS). The Hakai Institute will play a key role in the Pacific regional hub of CIOOS.

In late April, Hakai’s chief technology officer Ray Brunsting and data scientist Mat Brown attended a gathering in Washington, DC, of representatives from the now 12 North American OOSes. Brunsting and Brown spoke with counterparts about how to organize and make available the vast amount of data being collected 365 days a year.

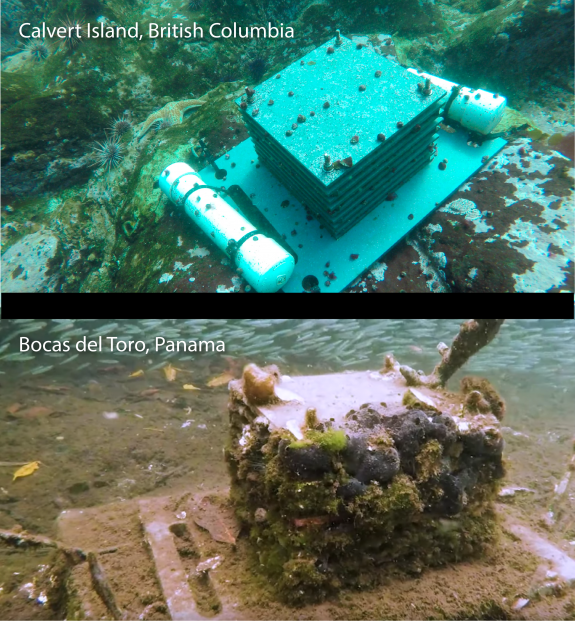

Less than two hours down the road, Hakai scientist Margot Hessing-Lewis was also participating in a gathering of scientific minds at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Virginia. Hakai’s Calvert Island Ecological Observatory is one of more than a dozen coastal research sites around the world, and the first in Canada, that contribute to Smithsonian’s MarineGEO network.

At this meeting, representatives from six countries set big picture priorities for the research network, solidified strategic partnerships, and planned future coordinated experiments.

“The MarineGEO network is building momentum and strengthening partnerships,” says Hessing-Lewis. “We are leading the charge when it comes to MarineGEO programming—cross-habitat observations, experiments in the field, and data management.”

Meetings across these various networks will continue through the summer and into the fall when even more collaborative initiatives will be kick-started at the once-in-a-decade OceanObs conference.

“The last conference in 2009 fired up the charge for expanded ocean observing related to marine CO2,” says Hakai scientist Wiley Evans. Evans added that he anticipates the 2019 meeting in Honolulu, Hawai‘i, this September will likewise spur broad oceanography programs.

Ahead of the OceanObs meeting, an international group, including Evans and Jackson, published a paper in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, which summed up existing coordinated oceanography efforts between Canadian and American agencies in the northeast Pacific.

“Our collaboration on ocean observing in the northeast Pacific is built on a foundation of shared goals,” says lead author Jack Barth, professor at Oregon State University. “We’re all concerned with doing the best job we can measuring and monitoring our dynamic, productive, yet changing ocean.”

So while the oceans remain a challenge to predict, collective efforts make sure that when they change, we’re there to measure it and advance our understanding.